La storia del confine orientale italiano non deve essere diffusa solamente in Italia, in quanto pagina di storia nazionale, ma anche all’estero, poichè tragedia europea del secolo scorso.

Condividiamo pertanto questo articolo in lingua inglese dedicato al Centro Raccolta Profughi di Padriciano (TS).

In 1954 Trieste experienced one of the largest refugee crisis in history. Sixty-eight years later, as Russian rockets hit Ukraine, history seems to sadly repeat itself with more than 1.5 million people having so far fled over the borders of neighboring European countries into a frightening and uncertain future.

Many Ukrainian refugees are reaching Trieste. In our city, a network of associations and volunteers are working hard to support these desperate people. However, as the United Nations warn, this is just the beginning. It is estimated that more than 4 million people will become refugees, while inside Ukraine millions more will be displaced. What we are witnessing is the largest refugee crisis in a century.

The last crisis of this proportion was at the end of World War II, where an estimated 11 million displaced people were registered across Europe. Displaced persons’ camps were primarily for refugees from Eastern Europe. However, in the Italian city of Trieste there were also thousands of Italians who had fled their homes in Fiume, Istria and Dalmatia after it was declared Yugoslavian territory. Trieste and its CRPs (Centro Raccolta Profughi – Refugee Gathering Centers) has had a long experience in dealing with refugees long before the Ukranian crisis.

An estimated 350,000 refugees coming from the former Italian territories of Istria, Fiume and Dalmatia reached the city in the years following the second conflict. The camps in Trieste were often the last stop for entire families, before they embarked on ships to take them to a new life. Some families stayed for a year, others much longer. Thousands settled in Trieste for good.

There were nine official camps in Trieste, but research about them is not an easy task. Their history, as well as their fading presence, seem to be an uncomfortable issue often kept confined to the past. One such place is the old refugee camp in Padriciano, in operation from 1954 to the mid 1970s.

This CRP (Centro Raccolta Profughi) was mainly for the Istrian refugees. Throughout the years in activity, it hosted between 5,000 and 7,000 people. It still stands today, partly abandoned, partly museum, partly bee farm, partly illicit dump. It was built in 1945 after liberation and used as military barracks by the Allied forces. It is forever to remain another silent witness of Trieste’s troubled history.

Located along the main road that connects the Carso villages of Basovizza and Padriciano, a tall and gloomy metal fence surrounds the vast site. Inside, dilapidated buildings and abandoned cars cover the area. A sign on a chained gate tells of a museum, which appears to be closed, except for special dates, such as February 10th, when Italy sadly remembers the thousands of Italian citizens killed by Yugoslavians during the retaliations that followed the end of WWII.

The museum itself, established by Unione degli Istriani of Trieste in 2004 and run on a volunteer basis, is a heartbreaking experience. Built inside one of the few standing stone barracks which functioned as the camp’s canteen, the cold, peeling walls tell of familiar tales we too often hear about. It is the timeless account of displaced people, among them many children, forced to flee their homes with little or no possessions.

A series of panels illustrate the historical and political events of the area and help understand the new lines of the border between Italy and Yugoslavia drawn in 1954 and the consequences they led to. The recreation of living spaces, literally no bigger than a container, allows us to imagine the difficulties that the exiles had in facing the years following their forced exile.

At the center of a large hall is a stack of furniture and everyday objects that tell of the hopes of so many people who sought normality in trying to recreate their former lives. Many photographs hang from the walls, and you can’t help being amazed at the smiles of young girls despite broken hopes and dreams.

The museum also contains objects dating from the Nazi and Titoist occupations of the city of Trieste, as well as original signposts (Istrian towns and villages) used for the gathering of exiles after their departure from their homeland. Outside the museum, a symbolic graveyard made of Carso rocks bears the names of some of the exiles.

Further away, in the vast area surrounding the few standing building, there is what remains of the sleeping quarters. The stone foundation of the barracks tell us of a place not much different from a concentration camp. Unheated wooden shacks with roofs in asbestos and divided into 4×4-meter boxes accommodated single families.

The precariousness of living conditions inside this structure, where entire families lived in cramped spaces separated only by blankets, sheets or, in the most fortunate cases, by simple plywood barriers, created a promiscuity that led refugees to live in constant uncertainty, not only related to unhealthy environs and precarious hygienic conditions, but also to isolation from the city context.

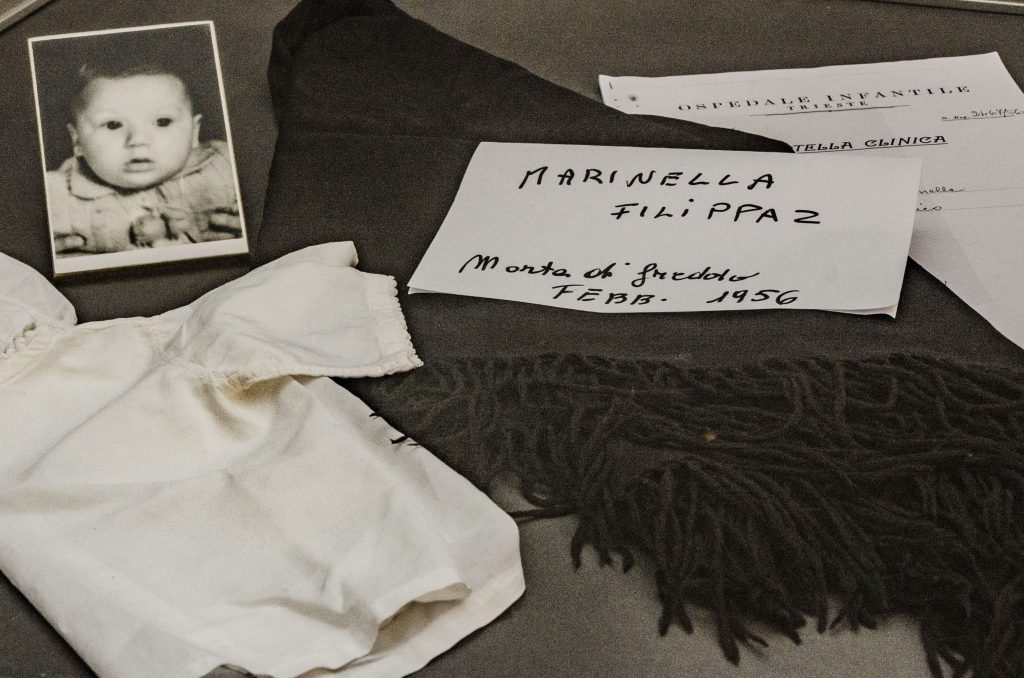

It was so cold inside the barracks during Trieste winters that children got very sick, and, in one recorded case, died. This is what happened to young Marinella Filippaz, who froze to death in February 1956. She was only one year old. The camp ended up becoming a world apart, totally foreign to the rest of the city, with its own life, times and rules.

The refugees had to cope with poor living conditions for over twenty years until the construction and assignment of new homes. This meant that a whole generation of Triestini were born and reached adulthood inside the barracks. It is estimated that by 1961 one third of Trieste’s population was made up of refugees.

You can reach the grounds of the old refugee camp through a tiny gate further down the road from the museum entrance. A yellow and green sign painted on it indicates the way to the abandoned grounds.

To plan a visit to the Padriciano refugee camp museum you can contact Unione degli Istriani +39040636098 www.padriciano.org, or write an email crp@padriciano.org

Alessandra Ressa

Fonte: In Trieste – 16/03/2022